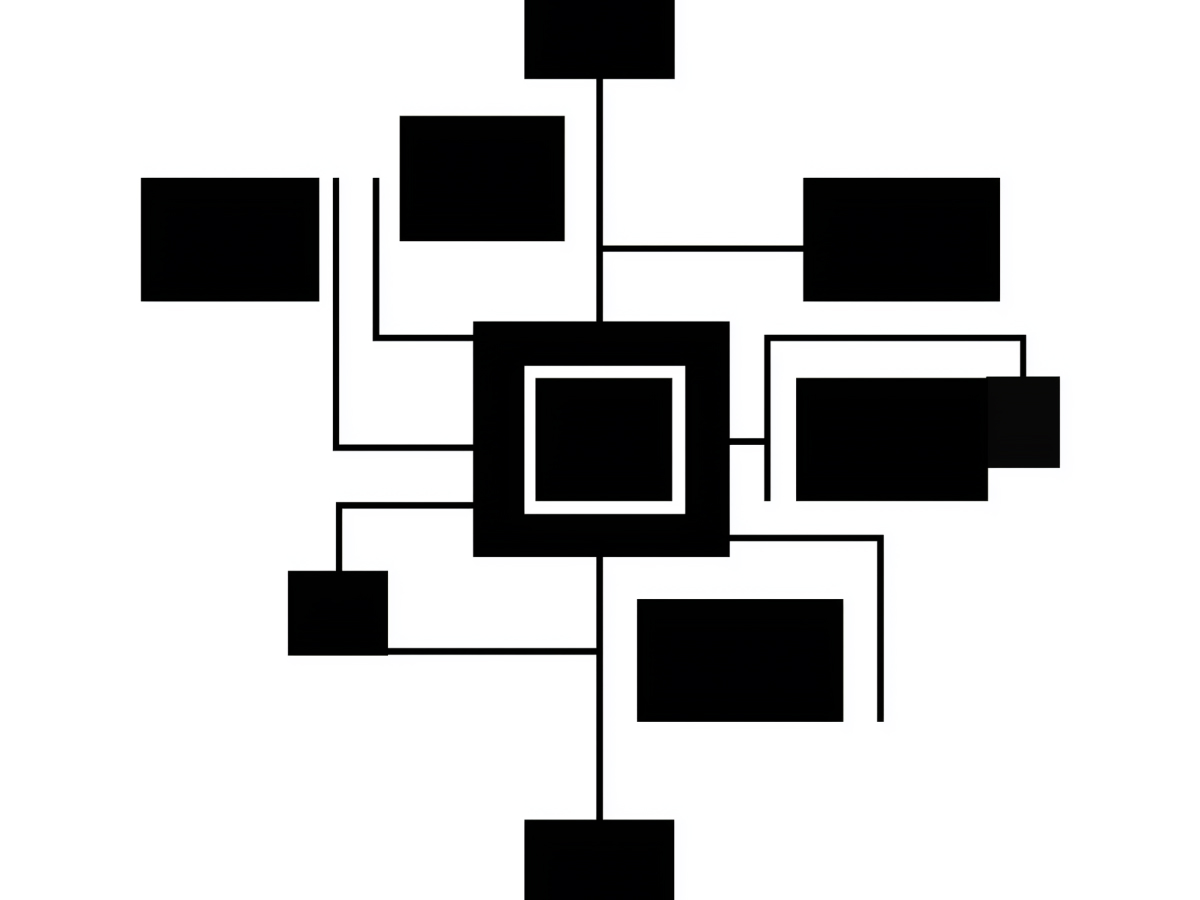

A system’s architecture inherently reflects an organization’s communication and structural dynamics

Melvin Conway said it back in 1968, and it hasn’t stopped being true: the way your teams communicate gets mirrored in your software architecture. This isn’t theoretical, it shows up in the alignment, or misalignment, of services, APIs, and infrastructure layers. If your teams are siloed, your systems will behave as if they’re siloed. If communication paths are fragmented, your architectures will be too.

This has operational implications. Systems that should be simple become complex. Services are hard to scale. Incidents take longer to resolve, not because the code is broken, but because no one’s quite sure who owns what. Architecture, in real terms, is shaped by the way decisions are made, how quickly information moves, and whether teams actually understand each other’s requirements.

So, before you reshuffle teams or greenlight a new platform initiative, take a hard look at communication. Who talks to whom? Who’s left out of the loop? You’ll probably find the reflection of that structure deep within your system diagrams. And if you want tighter, more autonomous systems, start by improving how your people work across boundaries.

This matters because the cost of misalignment doesn’t show up on day one. It’s later, when launching takes longer, scaling becomes painful, and new hires can’t onboard cleanly. Clear systems emerge from clear communication. Better architecture starts with better organization.

Most architectural problems originate from communication gaps

Most teams don’t miss deadlines or fail to scale because of some deep flaw in their codebase. It usually comes down to people not talking to each other at the right time, or not talking at all. Handoffs go wrong. Expectations don’t match. Teams make assumptions. And those gaps? They reshape your architecture into something brittle, slow, and resistant to change.

We often treat technical choices, frameworks, programming languages, deployment pipelines, as the big architectural drivers. But that’s not the real lever. The real shift happens when people share context early, when they surface assumptions before they become expensive, and when teams design intentionally, not just based on whatever structure they’ve inherited.

That’s not about adding more meetings. It’s about creating habits of alignment. Fast-moving organizations don’t always have perfect processes, but they create communication resiliency. They ask the right questions early, Who owns this? Who’s impacted? Have we agreed on how we’ll evolve?

If you’re a leader aiming to build systems that move fast and scale cleanly, start by fixing how your teams interact. Architecture doesn’t fail in code. It fails in silence, in skipped conversations, and in the space between teams that assume they understand each other, but don’t.

Eliminating that friction is less about tooling and more about behavior. Architects who focus on conversations, not just code, spot the breaks before they happen. That’s how you get systems that move fast and stay stable.

Architects operate in environments of ambiguity and must guide teams through uncertainty

Architecture doesn’t give you clean inputs or fixed rules. It deals with shifting requirements, undefined trade-offs, and long timelines. Predictability is low. Decisions must be made anyway. That’s what makes the architect’s role strategic, because in the absence of certainty, they create the clarity others move with.

Engineers often look for correctness. Does it work? Does it pass the test? Is it efficient? Architects work from a different lens. They handle decisions that can’t be proven right when made, only proven useful over time. A new service boundary, a quota system, a user permission model, these aren’t solved by logic alone. They require judgment under evolving conditions.

Most organizations still treat architecture as a point-in-time blueprint. That approach fails when priorities shift, stakeholders disagree, or when integrations reveal problems weeks after launch. The best architectural work doesn’t depend on perfect foresight. Instead, it builds resilience by aligning teams around shared constraints and flexible principles. Those guardrails let people adapt quickly when changes inevitably arrive.

For leaders, the lesson is simple: stop asking your architects for certainty. Give them the mandate to navigate ambiguity, and back them when decisions get hard. Because good architectural judgment isn’t about being right at design-time; it’s about creating systems that stay functional when things change.

Software structure reflects organizational misalignment as much as technical deficiencies

When a system becomes slow to change or hard to reason about, the issue is rarely just technical. More often, it’s organizational. Unclear ownership, contradictory priorities, and decision avoidance create environments where misalignment becomes architecture. Every delay, every duplication, every unnecessary workaround maps directly to confusion upstream.

If integration between two critical components is always a problem, look at the teams behind them. Are they aligned? Do they trust each other? Are incentives shared or competing? The breakdown often isn’t just in infrastructure, it’s in the absence of coordination between people. Misalignment creates drag. And that drag shows up in code: duplicated logic, patched bugs, and brittle systems that collapse under scale.

Architects can’t compensate for organizational blind spots. They can only expose them. And when those patterns appear repeatedly, they act as signals. Common ones: no one can answer who owns a component. Multiple teams think they each own the same system. Priorities change weekly, but no timeline adjusts. This tension gets felt by architects first, who see the disconnect between what’s possible and what’s politically allowed.

If you’re seeing repeated technical pain in the same areas, pause and look beyond the system. You’ll usually find gaps in management clarity, team structure, or accountability. Fix that, and the technology often becomes easier to manage. Architecture doesn’t overlook business structure, it reports on it. Leaders who ignore this do so at their own risk.

Frustration is a diagnostic tool indicating where structural misalignments live

Architects often experience a specific kind of frustration, one that surfaces when they know what needs to be done but can’t get the right support to execute. This tension arises not from incompetence or lack of vision, but from gaps in ownership, unstable priorities, or stalled decisions. The technical work is clear. What’s missing is a structure that can support it.

This frustration isn’t noise. It’s signal. It points to parts of the organization that don’t have enough clarity, where accountability is distributed unevenly, or where critical decisions are left unresolved for too long. Architects who understand this treat frustration as data. They don’t avoid it, they follow it.

When a team feels stuck, the underlying problem is often not architecture itself, but the absence of an environment where aligned decisions get made. Overlapping charters. Blurred product and engineering responsibilities. A senior leader unwilling to arbitrate trade-offs. These are not technical issues, but they produce breakdowns in technical execution.

If you’re a senior executive and your architects are constantly frustrated, it’s a cue that something deeper is wrong. And it isn’t just their problem to fix. It’s a system-wide structural issue calling for stronger alignment, clearer decision frameworks, and less political ambiguity. The faster you treat those signals seriously, the faster your teams return to delivering progress.

Systems mirror team structures; thus, architecture is a disguised form of organizational design

Architecture is not created independently from how your teams are structured. It reflects the boundaries you’ve set, the communication patterns you reinforce, and the coordination flows you support. Modern systems break along the same seams that organizations do. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a direct result of how companies operate.

Team handoffs become system interfaces. Microservices reflect team autonomy, or the lack of it. Integration complexity often shows up in areas where two parts of the organization don’t align effectively. Technical scale challenges usually point to mismatches in team scale, capacity, or delivery models. The architecture you have is the structure you’ve built into your company.

This is where architecture transitions from being purely technical into something deeply operational. Barry O’Reilly summed this up clearly when he said: “Architecture is decision-making in the face of ignorance.” Architects often face pressure to define systems that must scale, evolve, and safeguard the future, without complete information. They operate in a field where ambiguity isn’t a problem, but a permanent condition.

For executives, the message is simple: architecture problems are frequently organizational problems first. Investing in better collaboration models, clearer cross-team ownership, and more strategic team boundaries helps resolve both. If systems keep failing at critical pressure points, don’t inspect just the code, inspect how your teams are aligned. Good architecture can’t compensate for poor structure. But strong, aligned organizations inevitably support better systems.

Technical systems are inseparable from the social systems that sustain them

Technology doesn’t operate independently of the people managing and maintaining it. Software systems are built, adapted, and scaled by teams, real people with workflows, communication paths, and incentive structures. When systems break, it’s rarely just code that’s at fault. Something in the supporting human system stops working.

This isn’t a new idea. In 1951, Trist and Bamforth studied British coal miners and observed that when new technology was introduced without adjusting the existing team structures, productivity fell instead of rising. The lesson they recorded over 70 years ago remains relevant today. If you evolve your tech without evolving your teams, you generate friction.

You see this clearly when a new system goes live, maybe a microservices strategy or upgraded CI/CD tooling, but deployment intervals slow, or incident rates rise. That gap isn’t caused by inferior technology. It’s because ownership is unclear, processes haven’t been updated, or necessary knowledge hasn’t been distributed across teams. You introduced change at one layer but ignored the others.

That’s the reality leaders need to prioritize. Every technical evolution must include an assessment of the surrounding team dynamics. Communication patterns, decision-making routes, and areas of accountability all determine whether new tools actually improve delivery speed or stall it. If the people and structures don’t change with the tools, you’re just adding complexity.

Modern architects must prioritize platform thinking to reduce socio-technical friction

Architecture today is less about creating diagrams and more about reducing the friction teams face when building and shipping software. That’s where platform thinking comes in, it’s about designing environments that make the right behaviors easy, sustainable, and scalable. A well-thought-out platform removes obstacles instead of adding more rules.

Real platform design starts with understanding the experience teams have when moving work from idea to production. Where do delays occur? Where does effort get duplicated? Where does unnecessary risk accumulate? Effective platforms address those questions before suggesting tools. They embed best practices without heavy oversight. Developers don’t need to check boxes, they move faster because the environment is designed around their actual needs, not assumptions.

Good platforms are not just shared services or internal APIs. They are holistic ecosystems where decisions don’t need to be re-invented. Security is built-in. Monitoring is default. Tools are discoverable and well-supported. That kind of experience gives teams autonomy with confidence, they move fast without guessing at what’s safe or acceptable.

For C-suite leaders, this is where architectural investment pays dividends. Don’t just ask how resilient the system is, ask how easily teams can do the right thing. If your teams are bumping into compliance, infrastructure, or integration slowdowns, it’s not a resource issue. It’s a platform one. Investing here won’t just reduce operational risk, it’ll increase team velocity and deliver better products across the board.

The architect’s primary job is to shape the conditions under which systems can be successfully developed and maintained

Architecture isn’t just a design function, it’s operational infrastructure for decision-making. Good architecture creates the conditions for teams to move quickly, safely, and with minimal friction. The role isn’t to perfect every solution in advance but to set up decision frameworks that scale across people, systems, and time.

The most effective architects don’t just deliver models or diagrams. They reveal invisible dependencies. They write down the decisions others forget to track. They create systems where teams can onboard faster, where updates don’t break downstream systems, and where evolving product needs don’t corrode long-term technical stability. The value here is cumulative, it compounds as complexity increases.

This work is often quiet but highly leveraged. Documentation of architectural choices becomes reference points when questions arise months later. Identifying and mapping real-world constraints, who owns what, what’s scalable, which paths create future rework, gives teams clarity that’s difficult to replicate with reviews or testing alone. It’s not about gatekeeping velocity; it’s about enabling it with lower risk.

C-suite executives should view architecture as a force multiplier. It acts behind the scenes to prevent avoidable escalations, protect technical integrity, and institutionalize learning. If teams are constantly firefighting or revisiting the same decisions again and again, then the architectural environment isn’t working. That’s not a failure of execution, it’s often a failure of enablement.

Architecture is not just technical design, it’s the act of enabling organizations to design better systems

The role of the architect is evolving fast. Today, the best architects aren’t the ones enforcing compliance or selecting tools. They’re the ones shaping organizational habits that lead to better systems over time. They define how choices get made, how teams align on outcomes, and how uncertainty gets managed consistently across initiatives.

This work isn’t isolated to engineering. It influences how risk is handled across product strategy, how scalability is approached long before constraints emerge, and how complexity is managed rather than avoided. In this sense, architecture isn’t just about systems, it’s about evolving the operating model so teams become more capable, not just more productive.

Good architectural work tends to vanish into the background. Decisions that could derail alignment don’t. Teams solve problems early and move forward with conviction. That doesn’t happen by luck. It happens in environments where the defaults are strong, where guidance is available without bottlenecks, and where alignment is baked into the system, not imposed at the end.

If you’re in the C-suite, understand this: the ultimate measure of strong architecture isn’t how clean the diagrams are, it’s how effectively the organization builds, scales, and sustains system evolution. The architect’s long-term value comes from making that capacity durable, repeatable, and aligned with your business goals. That’s not optional. It’s foundational.

Architecture is a reflection of the real, not formal, operating structure of an organization

Architecture doesn’t reflect what’s written on an organization chart. It reflects how your teams actually operate. The informal networks, the people who own decisions, the friction points, the unspoken rules, all of that shows up in your systems. Every gap in clarity, every unmanaged dependency, every political delay maps cleanly into technical outcomes.

You can see this in how systems behave over time. An architecture might launch well but degrade quickly. Performance issues start piling up, integrations become brittle, and delivering features gets slower. The root cause usually isn’t the initial design, it’s that the system reflects real organizational habits that never got addressed. Code follows culture.

The difference between how your processes are supposed to work and how they actually work becomes measurable in your system health. Teams don’t wait for approval flows or documented escalation paths. They rely on the people they’ve built trust with. That’s why the architecture reflects interpersonal alignment more than formal governance. The system speaks the language your teams truly use, who people turn to, what priorities dominate, where ambiguity lingers.

For executives, this is a key insight. If you’re trying to improve architecture outcomes, don’t just evaluate technical documentation. Audit your own decision velocity. Look at how people push back on misaligned goals, or how often your teams avoid hard choices. Systems aren’t neutral, they reproduce the strengths and weaknesses of your company’s real behavior. Fixing the organizational model improves architectural clarity, reduces downstream failures, and creates systems that evolve cleanly without collapse. That should be the aim.

The bottom line

If your systems feel slow, brittle, or increasingly expensive to maintain, the problem isn’t just technical. It’s structural. Architecture doesn’t happen in isolation, it’s a reflection of how your teams work, where decisions get made, and how information flows across the organization. You can’t upgrade your systems without upgrading how your people operate.

The takeaway for leaders is clear: get closer to the friction. Don’t treat architectural pain as an engineering problem to delegate or defer. It’s often a signal that your operating model needs attention. Misalignment between teams, unclear ownership, and stalled decisions show up faster in your architecture than in your quarterly OKRs.

Create space for deeper architectural thinking. Invest in platform teams that remove barriers, not add control. Ask better questions, about ownership, coordination, and decision-making velocity. And when frustration surfaces, don’t mute it. Use it. It’s context-rich data showing you exactly where your organization is out of step with itself.

Strong architecture isn’t just smart design. It’s a leadership outcome. Treat it that way.